FLESH

On the new Booker prize winner

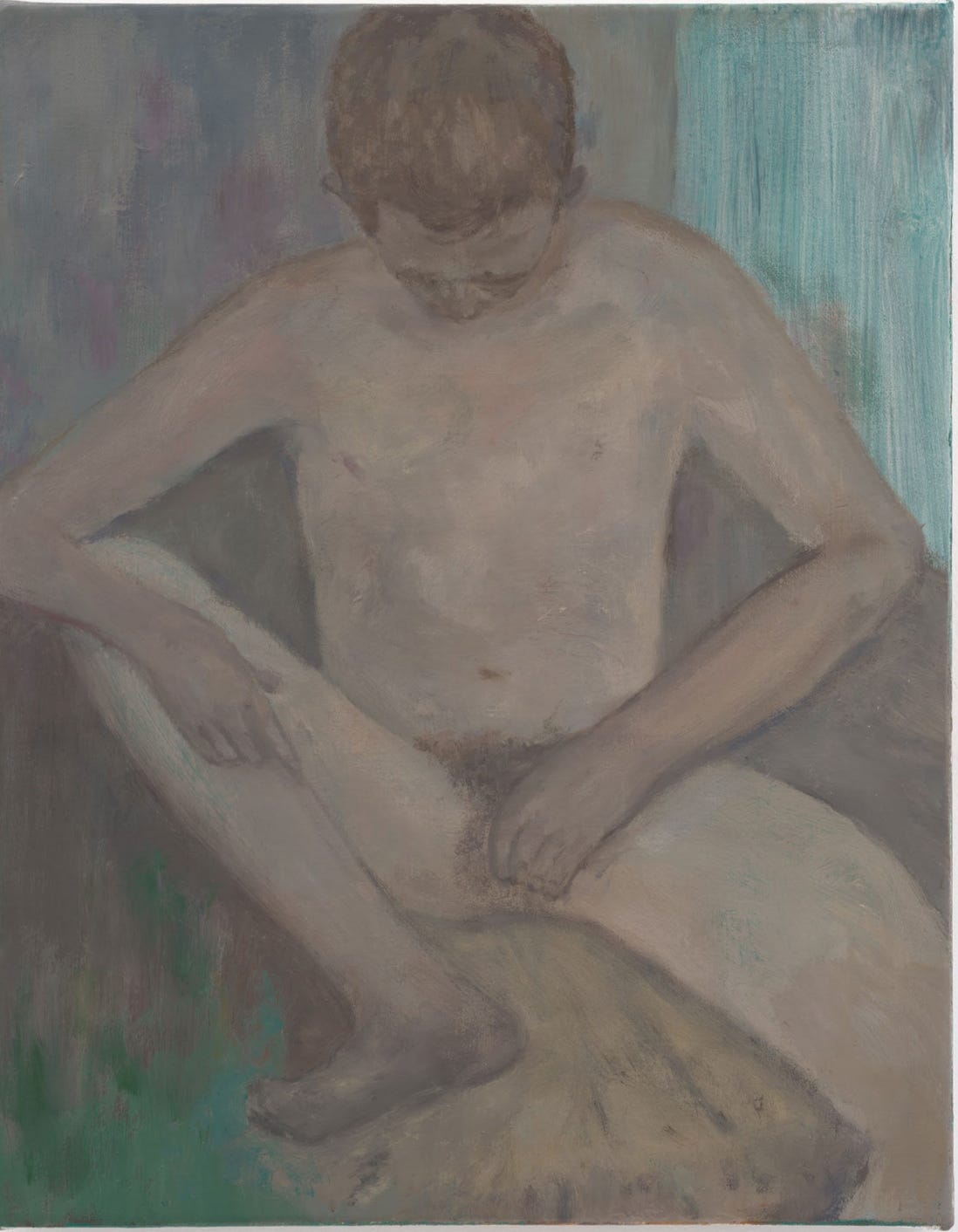

Shota Nakamura, Nude 1, 2024, oil on linen 38 x 30 cm

‘Flesh is the reason oil painting was invented’ quipped De Kooning. And indeed, thinking of Lucien Freud’s paintings, the absolute master of fleshy portraits, in which the skin feels warm to the gaze, rippling with desire and heat, oil seems to be the ultimate medium to give presence to flesh. So is fiction it turns out.

The winner of last week’s Booker Prize, David Szalay’s novel Flesh, is a rags to riches to rags story following a man, Istvàn, from his birth place in Hungary where we encounter him as a moody teenager to London where he works as a bouncer, then private driver and later property developer. It’s a portrait of masculinity and alienation that feels thoroughly new in the recent landscape of fiction. The hero is the heir to Camus’ Meursault. The narrator is profoundly detached, whatever his circumstances may be. Life seems to happen to him rather than him pursuing life.

What makes a good portrait in painting is not merely flesh, but interiority. There has been a lot of vulnerable depiction of male nudes recently - think of Louis Fratino’s lush portraits of queer intimacy, Shota Nakamura’s world of interiority, or Anthony Cudahy’s introspective portraiture. Male nude by male artists, depicting themselves or their lovers. In those paintings nudity and introspection go hand in hand, baring ones’ body to bare one’s soul.

In this novel, the exact opposite is at stake, the protagonist nakedness in the flesh, his raw state, makes him an object of irrepressible desire to women, and they are barred from his inner world. He is a piece of meat. Istvàn monosyllabic ‘yeah’ and ‘okay’ are - bewildering- profoundly enticing. It is a sparse novel which invites the reader to fill in the silences. We are denied access to his inner thoughts, which means we want to hear them all the more, and it is what makes this novel so successful.

As a teenager Istvàn embarks on an affair with an older woman (she is 42), which ends in tragic violence. This is an abuse that will shape the rest of his life. Almost every relationship he has with women after that is tainted by that early power dynamic: the woman is either older, or richer, and married, with a husband who needs to be erased. Teenage boys don’t seem to grow up and sulk murderously. Women are treacherous and husbands are cockholds. The shadows of Hamlet and his family are quite literally there when the hero’s stepson performs the play at school.

The book is a succession of visual vignettes: smoking on the balcony of the building on the housing estate where he lives with his mother, sitting at the kitchen counter of his neighbor and older lover, the changing light pattern of the jacuzzi in an anonymous bathroom in a drug fueled night, watching the light glisten on two women’s naked flesh—‘nice body’ he says to one, not ‘you are beautiful’, not a pledge for connection, just meat assessing meat.

David Szalay is a master at moving time along. The chapters flow with such ease from one to the next as years go by, always with a surprise, or plot twist which made me read the way I binge watch mini series, hitting the arrow for the next episode before it even has time to launch. I want to know what happens next. I am hooked.

If the plot from rags to riches felt a little cliché the overall coldness and distance made it believable. Rarely have I read a novel that gives so little in terms of the main character’s inner life and makes one feel so much for that very reason.